The Writer

Referring to the Valdor, the Natalis, and other artists from Liège, the Marquis de Marigny said to Louis XV: "Sire, that is the only nation that engraves our kings well." The nation he was talking about was the nation of Liège, maybe the former diocese of Liège, with its many keen observers, gifted craftsmen, lying between France and Germany. Its reputation has spread far beyond the Meuse basin.

The rich and ancient traditions of Walloon landscape painting have always been inspired by nature. In old times painters brought back to their workshop outdoor sketches, fleeting impressions captured and transcribed in a few lines on a drawing.

With no little exaggeration, Paul Fierens thought that landscape art could be summed up as follows: "before 1830, in our country just like anywhere else, all that was painted was the conventional scenery of tinplate rocks spiked with rigid pines".

During the nineteenth century, the Walloon landscape painters imbued with the local land (terroir), just like their predecessors, constitute a vast array of talent organised around two centres: Tournai, looking no doubt towards France, and Liège, close to the Germanic culture. The melting pot of that nursery of passionate artists is the Wallonia so close to our hearts.

As an "Anthology of Liège landscape painting between 1880 and 1950" with superb colour reproductions of paintings, the "Dictionary of the Liège school of landscape painters" is a noble and magnificent undertaking because the entry of a name from that period is a tribute to the artist, who is in no way in competition with the others. The paintings each of them have produced make up a part of our rich artistic and cultural heritage. The omission of any one of these names would be the most cruel of punishments.

Wallonia should delight in having men who care for its heritage, in particular its landscape painting. One such man is Jacques Goijen.

I can only quote Van Gogh (letter No 121, 1878, to his brother): "It is good to love as much as one can, because that is where true strength lies, and the one who loves a lot can accomplish great things, and what is done with love is done well."

Gonay Jean-Pierre

In the same way as our Ardennes painters are highly marketable on the other side of the Atlantic, our writers would do well to set up their easels on the edge of the great Canadian forests. With Jacques Goijen, everything is transformed into painting, and the finely honed sentences of the French language are the perfect vector for that transmutation.

In the same way as our Ardennes painters are highly marketable on the other side of the Atlantic, our writers would do well to set up their easels on the edge of the great Canadian forests. With Jacques Goijen, everything is transformed into painting, and the finely honed sentences of the French language are the perfect vector for that transmutation.

In the sumptuously described landscape, the great timeless hunt unfolds and takes our breath away until the final kill.

Everybody will appreciate hunting according to their beliefs and their sensitivity. It is my right to see only intolerable bloodshed, made even more unbearable because it is dressed up to be aesthetically pleasing, and because it mocks a tradition, its rites and its pomp.

By contrast, in the preface Jean Carrière, writer and Goncourt Prizewinner, who recently died, tells us that our heroes hunt "with love" (his emphasis). Well, in that case...

The fact remains that among "the elements of heaven and earth", the predator is of course mankind, and it is as if we have intruded on this small world of the idle rich, aristocrats of hedonism, scornful of the common people who to them constitute the rest of humanity. As the story unwinds, we are subjected to a proximity that soon verges on a sickness-inducing promiscuity. The Epicureanism advocated by that elite fails to hide its existential vacuum. The amorality of that elite makes us moral.

If the harshness of nature evokes Giono, we are in the end embraced by the nausea of Sartre.

This will help understand how far this novel goes in destabilizing, disturbing, destroying the imprudent reader, my brother, my fellow-man.

Jacques Goijen perfectly masters his art and his subject. What makes him write? Is it to be in communion with the aesthetics of his heroes or is it to stand aloof, behind the barrier of the fiction?

He alone can give the answer. For our part we should read "Le Maître de Céans" for what it is: a portrayal of the eternal rivalry of man to man and of man to Creation, over which man has been extending his domination since the oracles of the first chapter of Genesis.

Christian Fouarge

The character of Jack is fascinating, even if not the most seemly: his violence, his assumption that he is born with rights over people and things, his cruelty, make him an extraordinary and unusual person, an attractive character, but not someone you would necessarily like as a neighbour nor want to see repeatedly cloned!

The character of Jack is fascinating, even if not the most seemly: his violence, his assumption that he is born with rights over people and things, his cruelty, make him an extraordinary and unusual person, an attractive character, but not someone you would necessarily like as a neighbour nor want to see repeatedly cloned!

But what fascinates in Jack is his extraordinary communion with nature. He has a carnal relationship with it and the magic of the writing brings us the charms and the spells worked: this is real literature.

This feeling for nature - expressed without any sentimentality - is rarely found today, even in fervent environmentalists. With Jack, we are treading in the humus, our head is in the fragrant mists of tall trees and our finger is on the trigger as we tirelessly stalk the much-prized and respected wild game.

I have to admit that I felt intense emotion reading the many pages where Jack throws himself body and soul into our forests. What a delight for the senses! That is probably the greatest achievement of this appealing and original novel, and I am grateful to you for allowing me to share its powerful charms.

Pol ROUSSEAU.

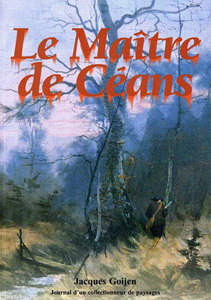

About the novel "Le Maître de Céans".

About the novel "Le Maître de Céans".

A letter in instalments

I have written you a number of times, but I hesitated when it came to posting. Sorry to have delayed. Here are the different stages!

Bouillon, October 1, 2004,

opening of the hunting season.

You told me: "I put my heart and soul in it". I enjoyed reading and feeling that part of your soul page after page. The fire that burns in the deer, in the hunter. Solitude while listening to nature and the restlessness of the city. I appreciated the stirrings, the hatred, the mists, the contrasts the silences, the quest for pictures, for the profound. The intensity of a separation as it unfolds to the point where blood spills. The communion between the deer as it dies and the human. All wrapped within a mutual respect, with the acceptance that the roles could be reversed.

Bouillon, November 11, 2004.

A day out hunting.

I have read your book. I am reading it again. If I had read your book a few years ago, I would have detested it without a doubt… hunting… hunters…

Some say that you see things in a different light once you reach 40. What a pleasure!

Later in November.

When clearing out my parents' house, I came across an old Larousse hunting dictionary. My brother and I practically argued over who would get to keep it! Hunting has never pursued me as much as it has done this year!

Bouillon, December 2004.

I have received the review of the book. I imagined the hours face to face with myself, with the book, beside the crackling fire, in La Roquarie or anywhere else.

Your writing, like the water of a stream, sometimes voracious, sometimes crystalline, sometimes cascading from one word to the next, direct, straightforward, not overburdened with detail, leaving the reader some liberty.

CDB.

Let me take this opportunity to thank you for your latest book that I enjoyed enormously. I found it one morning and I couldn't put it down. It will be with me for a long time. Having been fortunate enough to take a course in environmental consultancy, I was able to appreciate the true value of your book. Vocabulary, colours, odours and sensations that nature has to offer.

CP.

Tuesday, September 21, 2004 MIDI-LIBRE NÎMES

LEISURE

A novel by a Belgian author written in Lanuéjols

"Le maître de céans"

or the predator instinct

Hunting scenes in Quebec where man is a deer for man

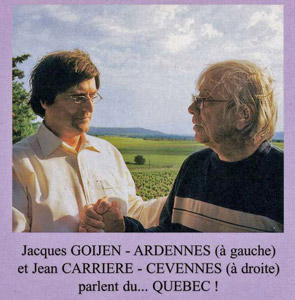

The setting could be the Cévennes since Jacques Goijen, although originating from the Belgian Ardennes, divides his time between Lanuéjols and Liège, where he is an art expert (1). It is hardly surprising that he has struck up a friendship with Jean Carrière, with whom he shares a taste for the wild beauty of nature. And it is Jean Carrière who has prefaced the novel "Le Maître de Céans" completed in Laroquarie (Lanuéjols) in January and hot off the press on July 5 (2).

A story told in the present tense, like a film script.

From being completely dominated by his adversary, the hero turns the tables to eventually assume the dominant role.

An art dealer who is a master of landscape descriptions.

Written in the present tense, this third novel by the Belgian writer, in love with the Cévennes after reading Jean Carrière's "L'épervier de Maheux", takes the reader straight into a story already in progress. Like an actor reading a film script, you unwittingly slip into the character of Jack, a hunter living in perfect harmony with the Quebec forest, who will find out who he really is - however horrible this may be.

Jack is a man who rejects the failings of a corrupted society he wants to leave in order to follow his instinct. In the end he has become a perverse and cleverly measured mix in which nature, that of the sublime scenery in which the action unfolds, but also his own nature, can also admit of cowardice. How does this happen?

We follow Jack, in search of truth, out stalking in a world of silences, rustlings and obscene bellows. With a certain curiosity first, then with growing anxiety, in anticipation of some tragic outcome, we unravel the complex web of his life, the reunion with a half-brother and a natural father, encountered by chance in a childhood memory.

Jack, the hunter, discovers in these men with their flamboyant heredity, and in the relationships they establish with women - mother or partner - and with himself, the same relationship as a dominant buck has with its group - the kind of domination that humiliates by taking possession of the other's material possessions, and even their very existence.

A (primitive?) scene, in respect of which Jean Carrière speaks of "torrid eroticism", serves to portray the abjection caused by this relationship between dominant and dominated. The excess is such as to give rise to an antagonism that feeds on animal instincts and human nature alike, with their mutual duality, and on acceptance and refusal. Dominated in the rut by the legitimate son, Jack comes out on top in hunting. Then begins a bloody duel, reminiscent of Cain and Abel, played out through hinds, hares and wild boars. The question is: who will emerge as victor from that savage blood bath to become more than just the dominant male, the real lord of the manor (Le Maître de Céans)? Will it be the predator or the hunter?

Therein lies the ambiguity of nature and human nature.

I was doubly moved in reading this book written by an author little known in our region. First of all by the detailed beauty of the hunting landscapes described by a writer who is a hunter himself - and an art dealer too -, a connoisseur of the world of hunting. The story would be excellent material for the big screen.

And second, having finished reading the book, you start debating with your conscience about the ambiguity of nature, the duality of human nature and the relationship between the two. The answers provided by Jacques Goijen, through his characters, do not please everybody. Proof, at any rate, that he must have hit his target.

Pierre RIVAS

(1) In particular those of the Liège school of landscape painting.

(2) For les editions de l'Ecole liégeoise du paysage. 198 pages, 20€.

The journey into the novels of Jacques Goijen is one of long steps, along paths of mystery, dreamlike realities, offering a response, confession by confession, to the Call that embraces, to the threat of artistic simplicity and passions.

"Le Maître de Céans"? A terrifying host of our own reflections, it stings our soul and our body. It has to do with overpowering emotion, lights of reason, strict truth, measure, passion, release, freedom, hope tangent to the absolute!

"The peace Jack is so passionately seeking seems uncertain to him in our neurosis-generating society which he utterly rejects." What can I say about Jacques Goijen? The burden of all that is past resting on his shoulders, a welcoming logic of the "why", "how", an inner voice directed towards the wide open and the unique light!

We can see this excellent poet, some kind of "quixotic Berlioz", defying the certainty of grand principles and imposed values, playing life, the incongruity of suspicion and certainty, for exhilarating stakes.

Maurice Pirotte.

I would tend to go along with C.F. and say "there is a part of the novelist in every single character", otherwise the content would lack depth and fail to produce the same impact on the reader.

What distinguishes your work is that dual view which accentuates the white and the black, and hence the gap that separates them. In your professional life you have bridged the gap by bringing the world of art into contact with the world of finance. You seem hesitant, unsure, in revolt, worn out by life's journey. But could you have borne to live any other life... faceless?

You may rest assured that in revealing to the world at large and to every enthusiast, in your compilation (the dictionary!), the love of nature and the passion of these regional landscape artists, you are offering a true treasure.

But a word of caution! I would counsel against laying so much emphasis on your rejection of society, lest this shroud the sensibility and the intellectual subtlety inherent in your book.

On the issue of hunting and the paradox of "being a hunter and being capable of compassion…" what I would see is more an osmosis between humankind and animal, a plenitude, the unexpected encounter with the other part of oneself: the spontaneous and instinctive nature of man.

Eliane Pironnet

The book contains some magnificent descriptions of nature, genuine impressions in close harmony with the paintings featuring in the story. The account of the young lads' expedition to the château is also skillfully crafted. It brings back childhood memories combining adventure and mystery.

In the first half of the novel, Jack is very much the good guy. His concern to rise above the superficial and artificial aspects of a trade of which he is a master makes him an endearing character. But we gradually come to realise that his pride (" The old buck would be worthy of dying by Jack's hand only if it has stayed remote from civilisation") is developing into murderous obsession: Jack, with his fixation on hunting, can only be himself if he manages to kill what he admires - a majestic deer - and also what he is envious of, meaning Boris, who behaves like a dominant male because he has been brought up by his father, while Jack has not had this privilege. Jack is totally self-centred, bereft of all sentiment save where it relates to his obsession. He becomes incapable of love for anyone or anything that does not serve his predator instinct.

And this sends shivers down the spine, because his contempt for mankind, he always being right while all others are wrong, makes him a monster, set in his belief that he alone knows the truth. And these are the worst monsters!

Think about it!

The people described in the novel are not the most appealing in human terms and it is understandable that Jack wants to keep his distance. But the way he acts (chooses to act?) shows him to be a hedonist incapable of any commitment save where it serves his own purpose. The character portrayed in the book is undoubtedly brilliant through and through, but we might ask, without moralizing, if he will ever manage to understand the meaning of the word "happiness".

I have my doubts about Jean Carrière's statement that Jack will descend to the wildness of animals when he hunts them "with love". (his emphasis.) That Jack does indeed sink to this level of wildness, there can be no denying, but however self-disciplined a true hunter might be, can we say that he kills his prey with love?

I could imagine that kind of relationship genuinely existing only in earliest man, in the dialogue that the hunter establishes with the animal he hunts by necessity. There is probably something of this still to be found in certain European hunting rituals.

This highly complex set of cravings and feelings becomes stronger and stronger as the story progresses to the point of demonstrating who exactly Jack is, a character worthy in some respects of André Gide, tracked relentlessly by the writer, but who does not, we dare hope, speak entirely in the writer's name.

Albert Moxhet